By John S. Forrester

Images from Peaceabbey.org

SHERBORN - Loudspeakers blare the Adhan, an Islamic call to prayer, into a neighborhood in this small, quiet Massachusetts town. As the few scattered visitors and staff stop, silently turning toward Mecca, the sun hangs high on the three acres nestled in Sherborn as the caller's calm Arabic phrases halts all activity. Near the road behind them is a 9-feet-tall statue of Gandhi, centerpiece of the Abbey’s pacifist memorial, just a few feet from the town’s war memorial. It’s an unusual juxtaposition, but it seems to characterize the against-the-grain nature of both the Peace Abbey and its dedicated founder, Lewis Randa, a conscientious objector during the Vietnam War who has been involved in social activism since the late 1960’s.

The Peace Abbey is a multi-denominational retreat center dedicated to educating the public about pacifism, social justice, veganism, and spirituality. Along with various classes, workshops, and a multi-faith chapel, the Peace Abbey has offered sanctuary, legal advice, and first-hand knowledge to dozens of members of the military who have gone A.W.O.L or deserted since 1991.

After high school in Des Moines, Iowa, Randa headed to the University of Iowa in 1966. During his junior year, the 19-year-old, worked as a member of the student coordinating committee for Robert Kennedy’s 1968 campaign for president.

“It was that campaign that led to the work I do today," Randa said, adding that the work of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. influenced him to become a pacifist.

While battles raged in Vietnam, the young Iowan felt the war's impact on campus as well. “The anti-war movement was palpable in the classroom, on the campus – because of the draft. There was really nothing else being discussed,” said Randa. Earning his degree in education, Randa says he joined the National Guard in 1969 to avoid the draft and service in Vietnam, expecting to serve in a stateside capacity, such as aiding civic projects and disasters.

Arriving at Fort Jackson in Columbia, S.C., for training, Randa knew his feelings had changed. “I believed at the time in the 'just war theory,' and I believed in the necessity of having a standing army. It wasn’t until I joined and went to boot camp that I realized I could not continue,” said Randa.

In order to leave the military based on a moral and ethical rejection of war, a soldier must clearly define in several essays what led them to reject violence. Before boot camp ended, Randa submitted his application. He then headed to Fort Drum near Watertown, N.Y., to participate in a summer training program.

“I was initially denied the 'C.O.' status I sought - and it required that I begin a fast, which led to my discharge, through the demonstration of my sincerity,” said Randa. After refusing to eat for a week and drink water for several days, Randa received troubling news. “I was sent back to Boston and told I would receive a discharge, only to be activated to Vietnam," explains Randa.

While in the city, he mentioned his situation to a few of Senator Ted Kennedy's staffers looking for help. Following a congressional inquiry, he was honorably discharged in 1971. Obtaining Conscientious Objector status 1-0, or a soldier who refuses military participation in any capacity, Randa had to complete two years of alternative civil service. In 1972, he founded Life Experience School Inc., to educate young adults with mental and physical disabilities.

“I agreed to perform 2 years of alternative service which is now approaching 35 years,” said Randa.

The Peace Abbey came into existence sixteen years later in the building next to the Life Experience School in Sherborn, after Mother Teresa - whom Randa met while volunteering in Calcutta in 1987 – came to visit him and the children. Following the visit in 1988, he was able to borrow enough funds for to create a center specifically dedicated to peaceful principles.

As Randa stands by the table where the renowned nun sat during her visit, he removes a necklace from under his shirt. “I give this to each ‘C.O.’ that processes their application. It’s the image of St. Francis of Assisi – make me an instrument of your peace – and on the back of it is a swatch of blood stained altar cloth of Monsignor Romero,” said Randa, referring to a El Salvadorian archbishop killed in 1980 the same day he urged revolutionaries to lay down their arms. “I make this available to wear during the process, it’s been worn by numerous people.”

One of Randa’s jobs is to aid in accessing a service member's values on violence and discussing options for resolving the issue with the military. He also performs services in the abbey as Massachusetts’ first Inter-faith Peace Chaplain, a pastoral role that embraces all religions.

While he spends most of his time informing strangers about activism and social issues, Randa often involves his family in his work as well. On the day that the current conflict in Iraq began, Randa and 17 other activists were arrested for civil disobedience after trespassing on the U.S. Army Soldier Biological and Chemical Command, an installation in Natick. He brought his three children, Abbey, Michael, and Christopher to watch. “Our kids are always allowed to get out of school to observe their father taking direct action, which leads to civil disobedience and arrest, but I always let them know that I do that with the belief that so long as we use non-violence to express our discontent… that it is something admirable and that they should feel good about,” said Randa.

Other than working directly with soldiers, The Peace Abbey is home to the the National Registry of Conscientious Objectors, founded by the center in 1991 – a list that people of any age or occupation can sign to declare their commitment to a life without using violence. Currently they collected over 1,000 signatures nationwide.

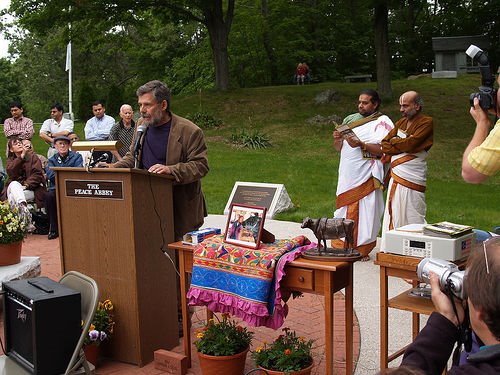

While not nearly as busy as other outlets of information for soldiers, such as the G.I. Rights Hotline based in Sacramento, Calif., the abbey offers services that hotlines and websites cannot: face-to-face consultation, access to legal representation, and a place to stay and contemplate while mulling over the next step, despite the fact that deserters are criminals who are subject to arrest. (left) Lewis Randa addressing a crowd at the Peace Abbey in Sherborn, MA.

Here, nestled among affluent homes in Sherborn, is where a few of America’s servicemen and women have been fighting a conflict - far from the roadsides of Iraq and the mountains of Afghanistan - of a deeply personal nature. In a wood paneled room within the abbey, the table where Mother Teresa sat during her visit - now called “the Peacemaker’s Table,” - is where Randa and other volunteers at begin discussing issues with service members when they visit the abbey.

“We will help them sort out their feelings as to the action they took because there’s a price to pay,” said Randa.

A report published in 2002 by the U.S. Army Research Institute, said the most common reasons for desertion are family problems, failure to adapt to military life, issues with the chain of command, and financial problems. Five percent of the 12,277 deserters quarried said they left for “other” reasons.

While many deserters intend to eventually return to their unit, a few service members – when faced with the violent realities of combat – decide, like Randa, that their personal morals or religious beliefs conflict with what they are taking part in.

“They’re going from place to place, staying with relatives, college friends, and they’re living with such upheaval, because they feel a phone call or an e-mail could lead the military identifying their location. What we’ve found is that there is a sense of hopelessness, because they can’t work,” Randa says, “they’re now dependant on others to finance their movement because they can’t earn a living and they can’t continue their education…this is a serious problem and we’re here to help people take the next step, when they’re ready.”

Between 2003 and 2005, 16,408 members of the armed services were classified as deserters, or a soldier who has been away from their unit or base for more than thirty days, according to data provided by the Department of Defense. It is unclear how many remain unaccounted for.

When asked how many deserters he was encountered through his work, Randa remains mum, though he estimates that dozens of soldiers have visited the abbey looking for information. “The doors are always open for people to find solace, support, and direction here. We don’t know how many soldiers come through here out of uniform, because we don’t ask,” Randa said. When someone arrives at the abbey seeking advice about desertion, Randa shows the visitor the abbey’s Pacifist Memorial, which features a bronze 6-foot statue of Gandhi and quotes from 65 influential pacifists. “When they start to read the quotes they get a better sense of what conscientious objection is all about,” says Randa.

Randa’s job – in a sense – is to clear up any confusion about the process and aid them in accessing their values. However they must object to all wars in totality - under the terms set by the military - rather than one war specifically. If the service member seems to meet the criteria and appears sincere, Randa says, then he helps them analyze their beliefs in order to develop a thesis about why they oppose the use of violence and specifically war.

“During times of conflict it can be anticipated that there will be a number of people who legitimately request CO [conscientious objector] status, then you have others who use it as a means to avoid fulfilling service obligations” said Major Sheldon Smith, a civilian reservist with the Army’s Public Affairs division, “In my opinion it’s a very fair process.”

What the military is looking for when judging conscientious objector cases, says Randa, is sincerity.

“There’s nothing that proves sincerity than taking your uniform and returning it to the military, which puts you in violation of the dress code. And you have to be able to say unequivocally I’ll go to prison.” “We ask them to consider joining various peace groups so they can get their periodicals, so that they can learn from people who have gone down that path. They have to realize what they’re embarking on there are thousands of people willing to reach out and provide assistance,” said Randa.

Aside from postings on their website, most of the Peace Abbey’s activities are advertised through word of mouth and grassroots methods.

“My mother was a member of an organization called Military Families Speak Out, and the co-founders live in Massachusetts. They had been to the Peace Abbey and they knew of Lewis Randa’s history, so they immediately made the connection,” said Sergeant Camillo Mejia during a phone interview from his home in Florida.

Mejia, who was living underground at the time, made his way to Sherborn by busses, trains, and walking to avoid detection. Mejia, who deserted his unit while on leave from Iraq in 2004, became one of the abbey’s most publicized cases. After spending several weeks at the Peace Abbey, reading about Gandhi, Dr. Martin Luther King, and other notable pacifists and preparing his arguments, he turned himself in at a press conference at the abbey.

“[Mejia] arrived here not fully understanding what a conscientious objection was all about. He needed to sort through for himself what this tradition involved, because when he refused to return, he knew that there were ethical reasons…but he needed to know that there’s this tradition he is part of,” said Randa. Randa later appeared at Mejia's court marshal for desertion as a character witness.

Despite potential criticism, Randa remains steadfastly dedicated to his work.

“We know that some people object to what we’re doing, they’re not all that vocal, but we know that there’s a degree of risk. We just hope people understand that we’re just helping people follow their conscience. We’re not telling people to do anything but follow their heart,” says Randa, “We’re not here to oppose anything, we’re here to support ones conscience.”